Sukhothai (The Dawn of Happiness)

A long bus ride (the one where we heard in detail the history of the Rama Kings!) took us 250 miles south of Chiang Rai to the Sukhothai Historical Park, a 45 square mile UNESCO World Heritage Site encompassing the ruins of a monumental ancient Buddhist city that rivals Angkor in Cambodia. A small Khmer military outpost built in the late 12th or early 13th century Sukhothai was, originally, similar in design to Angkor, with Hindu temples and intricate canals.

Over a period of about three hundred years, 11th-13th centuries, people from the region which is now south central China gradually migrated into the northern and central regions of what is now present day Thailand. These were the Tai people, called “Siam” by outsiders. They intermarried with the local inhabitants and established tiny city-states subordinate to Khmer rule in the areas in and around Sukhothai. As the Khmer Empire declined owing to years of warfare with their neighbors to the east, the Tai moved quickly to assert their autonomy and then their independence from their Khmer overlords.

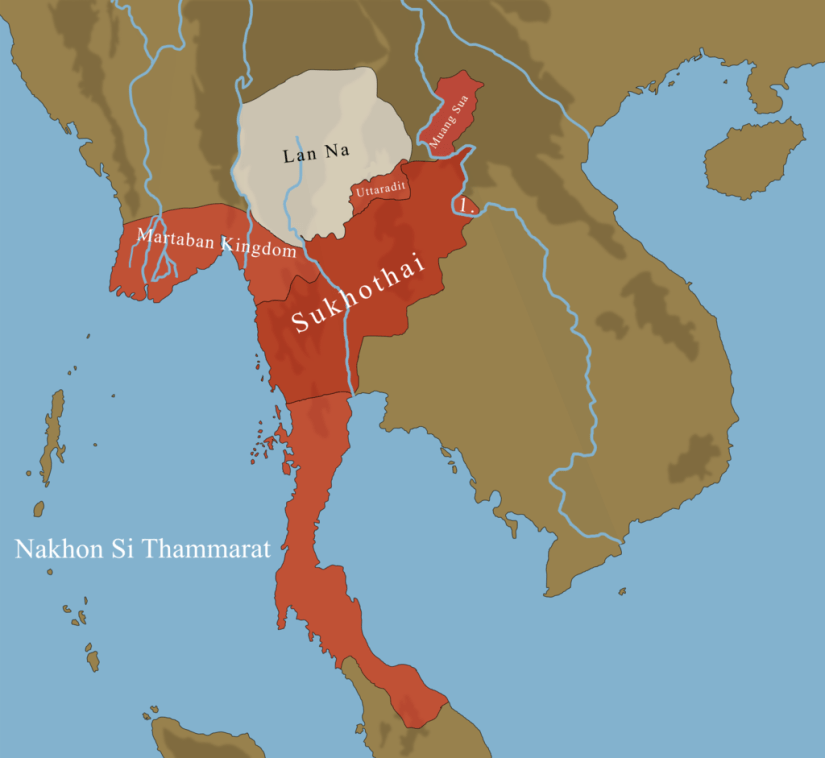

In 1238 a feudal lord, later known as King Si Inthrathit, united several city states into a single kingdom at Sukhothai and successfully defended it against the Khmer. A son of his, King Ram Khamhaeng, consolidated the kingdom, expanded its boundaries to the south and east, established Theravada Buddhism as the official religion and initiated trade with China.

For nearly 200 years Sukhothai flourished, partly because of its central location between the Khmer Empire to the southeast and the Burmese Kingdom of Pagan to the northwest. Although its diverse economy was based on agriculture, it became famous for the production of high quality glazed ceramics and exported them throughout Southeast Asia. It was also a center for the arts.

Under royal patronage Buddhism thrived. By the end of the 14th century Sukhothai was one of the largest Buddhist centers of the world. Buddhist monks were recruited from distant lands to live in the city with its exquisite monumental structures. Architects, engineers, skilled artisans came to build and decorate its temples and monasteries. The paintings, carvings and architecture associated with these temples and monasteries have a unique grace and eloquence, a style so distinct from Khmer and other regional styles that it is given its own name by art historians: “Sukhothai style.”

King Ram Khamhaeng is considered to be the author of the Thai alphabet. Hundreds of stone inscriptions found at the site give detailed accounts of the economy, religion, social organization and governance of the Kingdom of Sukhothai. It’s political and administrative systems are considered uniquely egalitarian for the time.

The prosperity and social harmony enjoyed by the inhabitants of Sukhothai derived in large measure from its amazing and innovative accomplishments of hydraulic engineering. Sophisticated dams, reservoirs, ponds and canals were created; water was controlled during times of drought or flooding. This management of water on a large scale served a variety of agricultural, economic and ritual functions. In this respect, Sukhothai is very akin to Angkor.

So much of what is considered uniquely Thai in art and architecture, language and writing, religion and law, was invented and developed in the Kingdom of Sukhothai that modern day Thais revere it as the birthplace of the Thai state. Sukhothai was its first capital city and King Ram Khamhaeng the Founding Father of the Thai Nation. In Sanscript, Sukhothai means “the dawn of happiness.” School children still memorize lines from a stone inscription dated 1283:

This land of Sukhothai is thriving. There are fish in the water and rice in the fields. The lord of the realm does not levy toll on his subjects. They are free to lead their cattle or ride their horses and to engage in trade; whoever wants to trade in elephants, does so; whoever wants to trade in horses, does so; whoever wants to trade in gold and silver , does so.

More images of Sukhothai ruins.

Ayutthaya (1351-1757)

After the death of King Ram Rhamhaeng, its vassal kingdoms began to break away from the Sukhothai mandala and a new rival Thai state to the south, Ayutthaya, began to challenge its political supremacy. Although by 1378 Sukhothai acknowledged itself a vassal state to this new power it continued to be ruled by local aristocrats and the two states merged only gradually over the next 150 years. Sukhothai’s rigorous military tradition, centralized administration, architecture, religious practice and language significantly influenced those of Ayutthaya.

The patchwork of city states that was the early Ayutthaya kingdom was centralized (1455) after its expansionist policies rendered it too large to be governed by the mandala system. By the mid 15th century it had acquired not only Sukhothai (and, in the process, sacked Angkor, thus ending its 600 years of existence) but a portion of the Malay Peninsula. Later it incorporated parts of Burma, Cambodia and the northern Thailand cities (Lan Na kingdom).

The city of Ayutthaya was situated at the head of the Gulf of Siam on an island surrounded by three rivers connecting the city to the sea, but far enough upstream to be protected from attack by the sea going warships of other nations. Halfway between India and China, it became an important center of trade and diplomacy at the regional and global levels. Europeans, initially the Portuguese but later Dutch, French, and English trading companies were given permission to trade in the kingdom. Enclaves of foreign traders and missionaries were established. Foreigners from many lands served in the civil and military administrations. The result was one of the world’s largest (probably a million inhabitants at its peak) and most cosmopolitan urban areas of its time.

As befits a wealthy, cosmopolitan connecting point between the East and the West, the arts – performance, literature, architecture – flourished in Ayutthaya. Theatrical performances of classical drama and dance (khon) originated in the Royal Court and were initially performed only there, but later spread and importantly influenced the development of the art in all of mainland Southeast Asia. Although in ruins, the large temples and monasteries are testimony to the technological skill of their builders. They were decorated with the highest quality of crafts, an eclectic mixture of regional art styles with those from India, Persia and Europe. This fusion of styles in art and architecture has characterized succeeding Thai eras.

The Historic City of Ayutthaya is another UNESCO World heritage site. The ruins here are really ruins, all that remains after the Burmese sacked and burned the city for seven days and seven nights in 1767. Centuries long wars with Burma (now Myanmar) and nearly continuous dynastic struggles finally destroyed the Ayutthaya Kingdom. It’s art treasures, the libraries containing its literature and the archives of historical records were almost totally destroyed. What is known about the kingdom and its 34 rulers has been gleaned from old maps, such as the one shown above, and accounts of foreign visitors.

More images of Ayutthaya ruins.