Origins and Rise to Power

Because of the absence any significant Etruscan written records or literature we must rely on historians and writers from contemporary or later cultures, usually Greek or Roman. These are not, however, unbiased sources: the Greeks were so envious of Etruscan dominance of the sea that they refer to them as “pirates,” the Romans were so anxious to claim credit for the founding of Rome that they create an origin story of divine ancestry, and both are so utterly appalled at the high status accorded Etruscan women that they were portrayed as immoral harlots. Thus one must read the accounts of ancient writers in the context of the times and take with a grain of salt critical, self serving commentary. Fortunately this is becoming more common in current writings and studies of the Etruscan civilization.

It is no exaggeration to say that the controversy over the origins of the Etruscans has been raging for over 2000 years. Ancient writers, with one exception, believed they had immigrated en masse from the near East or from the Aegean Sea region. Others, including modern Etruscologists, think they were indigenous to central Italy, perhaps deriving from northern Alpine tribes. The late Graziano Baccolini, an Italian chemist turned Etruscologist (and therefore a man after my own heart), suggests it is more important to consider the origins of the Etruscan advanced culture which was in contrast to the primitive culture of other Italic people. He compares the development of the Etruscan nation and culture to that of contemporary America. A continuous steam of immigrants who find a region rich in natural resources and who bear sophisticated knowledge of metallurgy, hydraulic engineering, building, etc., results, over a period of centuries, in a new cultural center and a new economic power. Thus he comes down to a quasi-orientalist point of view, an acknowledgement that the people who had lived there for centuries were influenced by wave after wave of immigrants, occurring over further centuries, with the resulting amalgam an entirely new culture.

The oldest Etruscan artifacts date from about the 10th century BCE. but, as Baccolini points out, increasing sophistication and the rise to power was gradual. Urbanization, massive clearing and drainage of land with the resultant agricultural bounty, plentiful metal deposits along the coasts, vasts forests that supplied wood for shipbuilding and housing, all contributed to a higher standard of living and a rapid increase in population. Trade, especially in minerals, expanded and the Etruscan aristocracy grew in wealth and power (and built elaborate necropoli outside the major cities from which we learn about their religion and lifestyle). By the mid 6th century BCE, the Etruscans were undisputed masters of the Tyrrhenian Sea and formidable rivals to the Greeks and Phoenicians everywhere in The Mediterranean Sea, a true thalassocracy.

Etruscan advanced trade networks not only covered the Mediterranean but extended into northern and eastern Europe, and the Aegean. Etruscan artifacts have been found as far north as Sweden and as far east as South Russia. Exports included wine, olive oil, grain, pine nuts, wood, marble, copper, iron ingots, bronze ware, linen, pottery and fine jewelry. Imports included gold, ivory, ostrich eggs (which were decorated and exported), scarabs from Egypt, fine furniture, glass bottles, oil lamps, and pottery, especially fine Greek pottery from Attica, the southernmost peninsula of Greece that includes Athens and its countryside. This latter import was so popular that some were made especially to suit Etruscan taste. More Attic pottery has been unearthed in what was once Etruria than in all of Greece. The Etruscans made and exported their own unique earthenware pottery called bucchero. It was black and often highly polished (reminding me of the famous Maria Martinez pottery from San Ildefonso Pueblo just up the road from me). The styles and decoration of this and other red clay pottery evolved over time as the Etruscan and Greek ceramicists influenced each other.

The two handled bowl was an Etruscan innovation

Attic styles influenced Etruscan potters. This appears to be a style called Attic Red Figure, a reversal of the dominant style in the figure/background color relationship

Decorated

handles were common

Etruscan Society

Governance

Etruria was a collection of independent city states bound by a common religion, language and culture. They developed independently so that advances/changes in governance, manufacturing, art and architecture occurred at different times in different places, with the coastal cities evolving more rapidly owing to their greater contact with other cultures. Although a number of city states banded together into Etruscan Leagues these were not political or military alliances; they were more economic and religious confederations. Early monarchies gave way to oligarchies in most city states, with the chief magistrate – who was the civil, military and religious leader – elected for a proscribed period by the aristocrats and, later, a growing class of merchants and landowners who aspired to join the ruling oligarchy.

Religion

Numerous sources describe the Etruscan government as a theocracy and it does seem clear that their religion was a central force in daily life as well as a source of inter state cohesion. Like other ancient civilizations, the Etruscans were polytheists. Extensive iconography on tombs and vase paintings, statues, engravings on the backs of bronze mirrors, give scholars an idea of the Etruscan pantheon, a blend of elements of Greek and Italic mythology and beliefs. The fundamental belief was that the universe was ruled by the gods and the fate of humans was completely in their hands. All natural phenomena conveyed the intentions of the gods and required interpretation to comply with their wishes.

Roman historians considered Etruscans the most religious of peoples and called their system of beliefs and rituals Etrusca disciplina, where the Latin word disciplina means “a science.” It was a complex system of codified ritual that included special divination disciplines, as well as rules for interpreting signs and portents and the responses to them to avoid disaster and placate the gods. Latin writers frequently refer to three categories of sacred books none of which survived the burning of the books: the books of thunderbolts, the books of haruspicy (divination based on the examination of livers of sacrificed animals) and the books of rituals. The basis for the scared books were revelations given by the gods to humans through a divine child called Tages. Thus the Etruscan religion, like Judaism and Christianity, was a”revealed” religion, considered not the work of human beings.

Experts in the Etruscan national religious science, called, generically, haruspices, were from high ranking families and were recognizable by their distinctive dress. The sacred books were handled down from one generation to the next and special training institutes provided instruction not only in theology but in subjects ranging from astronomy to botany to hydraulics, more like a university than a seminary. Even after the Roman conquest of Etruria, the haruspices flourished as the Romans, impressed with the practical benefits of the Etruscan discipline, were quick to employ the skills of these specialists. Emperors and generals had haruspices in their retinue, to be consulted when some event requires ritual or divination. The Order of Sixty Haruspices, drawn from the nobles of various Etruscan cities was created by the Roman Senate and served as that body’s expert advisors.

Art

As mentioned above, the Etruscans were skilled potters, also goldsmiths, but for me the most compelling of their art was sculpture and painting. Unfortunately, what remains is mostly funerary sculptures and frescoes giving us a skewed view of Etruscan art since only the very wealthy could afford tomb wall paintings. Still, given the lack of written documents, we rely on these to gain insight into the Etruscan lifestyle, at least some parts of it.

Sculptures were of terracotta, bronze or alabaster, rarely stone. Many small terracotta figures have been pierced together from fragments and life size figures reclining on the tops of sarcophagi (also made of terracotta) have survived intact, although only traces of the polychrome painting are left.

Monumental terracotta statues of deities adorned the rooftops of temples, an Etruscan innovation.

Their contemporaries considered the Etruscans to be undisputed masters of bronze casting. Etruscan metal craft and bronze sculptures were prolific in Etruria and across the ancient world. Ancient historians report that 2000 bronze statues were taken in the looting of Volsinii by the Romans and then melted down to produce bronze coinage to finance their wars. Whether or not this is true it is testimony to the great wealth, luxury and art of that city. Many small bronzes and mirrors (which were cast as one piece, highly polished on one side and decorated on the back) have been recovered but almost nothing remains of the large statues. The stunning Chimera of Arrezo gives us a glimpse of what has been lost.

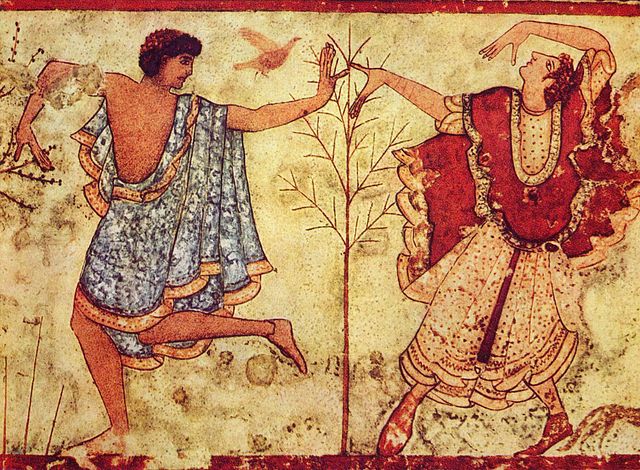

Dancers, Tarquinia, Tomb of the Triclinium

Photo: PD-Art-YorckProject

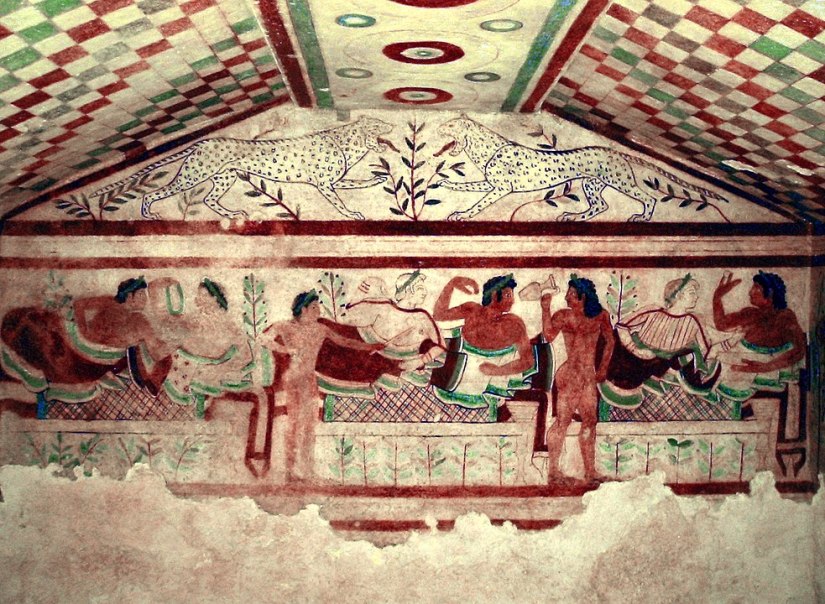

Tarquinia, Tomb of the Leopards, banqueting scene below, confronting leopards above.

Photo by: AlMare, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Much of what we know about Etruscan life derives from their many excavated tombs which, in the earliest times, were built with the assumption that the deceased would be active in the afterlife and thus have need for a dwelling complete with furniture, implements and decorations. Frescoes showed scenes from daily life, often banquets accompanied by dancing and music and games. Creatures and scenes from Etruscan and Greek mythology appear, and all of this in blazing technicolor.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

From these depictions and other works, the Etruscans come across as a fun loving, artistic culture that held women in high esteem unlike their Greek and Roman counterparts. Etruscan women dined and drank and danced with their men, were free to go out in public, attend sporting events and public celebrations, ride horses astride, raise their own children. They were literate, had their own names and ranks and could inherit property; they were beautiful and flaunted their beauty in public, wearing fine clothing and fabulous gold jewelry. Etruscan priestesses and oracles, while not prominent in religious practice, were in the public eye, influencing politics by their prophesying or giving blessing to newly elected kings. It is this public face of Etruscan women that seems to have scandalized contemporary Greek and Roman writers who then proceeded to vilify them. Clearly, those intensely patriarchal cultures felt a threat to the status quo which they sought to neutralize by characterizing the Etruscans as uncivilized barbarians. Ironically, the Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized couple pairing and valued multi-generational family ties.

The Decline

The seventh and final Etruscan king of Rome was overthrown in 509 BCE leading to the establishment of the independent Roman Republic which then attacked Etruria from the south. Maritime defeats and attacks on the port cities as well as invasion by Celtic tribes in the north continued the deterioration. By the mid 4th century BCE, the once dominant military and commercial power in the Western Mediterranean was reduced again to city states who failed to unite against a common enemy. Over a period of 234 years – years of wars, treaties, truces, alliances, sieges, counterattacks – they were picked off one by one by the more organized Romans. In the wake of those military defeats and the brutal colonization that followed much of Etruscan cultural heritage was lost.

A note about process

Those following this site may have noticed the long period of time between the last several posts. Lay it all at the feet of those “mysterious” Etruscans! One of the sources I consulted warned that once introduced to this amazing civilization one may quickly become hooked on the subject. So it was with me. I found myself spending hours delving into one aspect or another, seeking multiple points of view and interpretation, drawing my own conclusions from the mix, then trying to succinctly describe what I had learned, a very slow process indeed. I ended up using more images from other sources (all credited properly) as this post became more about ancient history than travel. If I had done this research before going to Tuscany it might have been a very different trip.

In case you want to explore more here are some interesting web references.