Click on an image to enlarge it.

where I share travel photos and experiences

Click on an image to enlarge it.

Deep in the lush south Tuscan countryside on a small mountain top not far from the Tyrrehenian Sea seekers will find a magical garden of huge sculptures inspired by the Tarot and encrusted with psychedelically colored mosaics and glass. This is the fabulous Giardino dei Tarocchi created over a fifteen year period by the French-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle who set out, among other objectives, to demonstrate that “a woman can work on a monumental scale.”

I had read about the Tarot Garden in one of those “hidden Tuscany” articles travel publications often feature and was keen to see it. Fortunately Marzia was also interested and we took off once again south, to the sea. Of course a meal was required and the tiny village in the vicinity of the Garden did not look promising. The one apparent restaurant looked pretty run down to our American eyes and on our own we’d have probably gone hungry. Marzia to the rescue! After huddling with the proprietor she lead us out to the table on the front porch where we were served, family style, a sumptuous fresh seafood feast: mussels appetizer followed by pasta with clams in the shells, then calamari and a green salad with a macchiato to keep us awake for the Garden.

We didn’t really need the macchiato as the Tarot Garden is so exuberant, so colorful, so full of life and joy that I can hardly imagine ever going to sleep there. Yet sleep there Niki did, living part of the time during the long construction period inside the mammoth sculpture of The Empress, the first built of 22 enormous sculptures representing the Major Arcana of the Esoteric Tarot.

Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002) was born in France into an aristocratic family whose financial misfortunes led them to immigrate to America, settling in New York City when she was three years old. Both parents, he a banker and she a fanatically strict American Catholic, were temperamental and violent and Nike described her home life as hell. Two of her siblings committed suicide as adults. She continuously rebelled, was thrown out of several schools as a teenager. A wispy, blue-eyed beauty, Niki was modeling at age 18, appearing on the covers of Vogue and Life. She married not long afterward and bore two children. The role of wife and mother assigned to her by society (not to mention years of sexual abuse by her father starting at age 11), was anathema to her, so much so that she ended up in a psychiatric hospital in Nice for six weeks. There she was encouraged to take up painting and other hands on artistic projects and discovered not only their healing qualities but an outlet for her contrariness, her fearlessness, her unquenchable life force, an outlet that defined the trajectory of her life. She later remarked “My mental breakdown was good in the long run because I left the clinic a painter.”

It is almost impossible to succinctly describe Niki’s prolific and turbulent artistic career after, in 1960, she finally gave up the obligations of everyday family life to create art full time. Self-taught, working outside mainstream art institutions (indeed, thumbing her nose at the art, religious and political establishments), constantly experimenting with new styles, techniques and materials, she soon found cohorts in the avant-garde French New Realists; she was the only female member.

Her earliest works, which she called Tirs (shootings), were aggressive, violent expressions of rage which attracted media attention and gained her notoriety in Europe. Large boards were covered with plaster in which was embedded bags and/or spray cans of multicolored oil paints, razors, baby doll limbs, crockery and other household detritus. Niki would then, in a staged public event, shoot at the assemblage repeatedly with a rifle or pistol, causing it to “bleed,” creating through destruction, combining performance, body art, sculpture and painting. These “happenings” expanded to art galleries, museums, private functions in Europe and the United States where other artists and even the public were invited to shoot at the assemblages. Participating in an unusual program of multiple, transformable artwork editions, Niki created a limited number of Tirs assemblages for purchase including detailed instructions for how to shoot them with a .22 rifle. A fascinating analysis of this work in the context of art at that time and the personal significance for Niki can be found in a publication of the Walker Art Center.

The Tirs period lasted only a couple of years after which Niki turned her attention to protesting the stereotypical roles of women in society by creating life size sculptures of brides, whores, monsters, mostly in soft materials. These evolved into her best known and most prolific sculptures, which she called Nanas , a French slang word meaning, roughly, “babe” or “chick”. Working with fiberglass reiforced polyester resin and gloss painting techniques, Niki was able to create monumental pieces that could be outdoors in all weather. Larger than life, voluptuously exuberant, intensely colorful, the Nanas reflect a more optimistic view, projecting indomitable feminine energy: “From provocation I moved into a more interior, feminine world.” These sculptures were exhibited widely in Europe at the time and public installations ( art “without intermediaries, without museums, without galleries”) still exist there, in Israel and California.

Niki’s work was classified as Outsider Art, a term for those who had a self-taught style, lying outside the defined “norm.” Her work was often dismissed, especially by American critics. Today she is receiving long overdue attention and appreciation.

Although Niki continued to create Nanas for the rest of her life, successfully commercializing them in different media in the face of sniffing disapproval from the art establishment, in the early 1970’s she turned her attention and energy to a long held dream: the creation of a mystical, magical sculpture garden of joy, a monumental expression of her own spiritual universe. The dream dated back to 1955 when she was awestruck by the flowing organic forms, diverse material usage and vibrant colorful mosaics of Antoni Gaudi in Barcelona. His use of shapes found in the natural world to create a dialogue between sculpture and nature spoke to a deep naturalism in her which rose to the fore years later.

With an introduction from their sister, a friend of Niki’s from her modeling days, two wealthy Italian brothers were won over by Niki’s charm and enthusiasm for the project and gave her a sizeable chunk of land, 14 acres atop an Etruscan ruin by the sea. Thus began a 15 years saga of difficult and intensive work, from creating the colossal sculptures to finding financial support to winning over local skeptics to coping with debilitating illness. Here are Niki’s own descriptions of the process. If you go to the cited article you will see that her purpose was to credit all the people – and there were many from all over the world – who worked with her to create this astonishing place. I have left out the names to focus on the process.

…All of the monumental sculptures armatures were made from welded steel bars, formed by brute strength on the knees of the crew….

Once the steel armatures were finished and the wire mesh was stretched over them, they were ready for gunite cement which was sprayed on. The sculptures then had a melancholy look with a certain sad beauty. My purpose, however, was to make a garden of joy. The finishing of the cement was later done by hand…

The twentieth century was forgotten. We were working Egyptian style. The ceramics were molded, in most cases, right on the sculptures, numbered, taken off, carried to the ovens, cooked and glazed, and then put back in place on the sculptures. When ceramics are cooked there is a 10% loss in size, so the resulting empty space around the ceramics were filled in with hand cut pieces of glass…

The smaller pieces in the garden were made by me in Paris, France…then fabricated in polyester…later covered in glass mosaics from Murano, Czechoslovakia and France…

I have chosen to respect the natural habitat of the region. The dialogue between nature and the sculptures is a very important part of the garden…

Niki de Saint Phalle

The Tarot Garden was formally opened to the public in 1998; by then Niki had moved to La Jolla, CA, because of declining heath. Despite handicaps she continued to explore new techniques, new media and became an active member of the San Diego art scene. She also continued to design additions for the Tarot Garden, including a wall and entrance way to clearly delineate the garden (“…a place to dream.”) from the outside world. In 2002 she died of respiratory failure, attributed to the years of inhalation of fiberglass and toxic fumes from her art making processes. As previously specified, all new work in the Tarot Garden was halted and the focus now is on preservation and conservation.

Rather than a post, I have chosen to make a Travel Gallery page showing the sculptures I photographed in the Tarot Garden. Please go there to see these magical figures and for more information about the individual representations of the cards. Notice that there are (sometimes hard to see) links in several of the image captions. Many are from a site devoted to mosaics and contain interesting descriptions of the symbolism of the pieces.

With renewed interest in her work, especially as it has been re-examined in light of the 1994 publication Mon Secret revealing her childhood sexual abuse, many articles have been written about Niki de Saint Phalle. Here are some I found to be particularly insightful. All of the references below were accessible as of 09/25/2021.

Because of the absence any significant Etruscan written records or literature we must rely on historians and writers from contemporary or later cultures, usually Greek or Roman. These are not, however, unbiased sources: the Greeks were so envious of Etruscan dominance of the sea that they refer to them as “pirates,” the Romans were so anxious to claim credit for the founding of Rome that they create an origin story of divine ancestry, and both are so utterly appalled at the high status accorded Etruscan women that they were portrayed as immoral harlots. Thus one must read the accounts of ancient writers in the context of the times and take with a grain of salt critical, self serving commentary. Fortunately this is becoming more common in current writings and studies of the Etruscan civilization.

It is no exaggeration to say that the controversy over the origins of the Etruscans has been raging for over 2000 years. Ancient writers, with one exception, believed they had immigrated en masse from the near East or from the Aegean Sea region. Others, including modern Etruscologists, think they were indigenous to central Italy, perhaps deriving from northern Alpine tribes. The late Graziano Baccolini, an Italian chemist turned Etruscologist (and therefore a man after my own heart), suggests it is more important to consider the origins of the Etruscan advanced culture which was in contrast to the primitive culture of other Italic people. He compares the development of the Etruscan nation and culture to that of contemporary America. A continuous steam of immigrants who find a region rich in natural resources and who bear sophisticated knowledge of metallurgy, hydraulic engineering, building, etc., results, over a period of centuries, in a new cultural center and a new economic power. Thus he comes down to a quasi-orientalist point of view, an acknowledgement that the people who had lived there for centuries were influenced by wave after wave of immigrants, occurring over further centuries, with the resulting amalgam an entirely new culture.

The oldest Etruscan artifacts date from about the 10th century BCE. but, as Baccolini points out, increasing sophistication and the rise to power was gradual. Urbanization, massive clearing and drainage of land with the resultant agricultural bounty, plentiful metal deposits along the coasts, vasts forests that supplied wood for shipbuilding and housing, all contributed to a higher standard of living and a rapid increase in population. Trade, especially in minerals, expanded and the Etruscan aristocracy grew in wealth and power (and built elaborate necropoli outside the major cities from which we learn about their religion and lifestyle). By the mid 6th century BCE, the Etruscans were undisputed masters of the Tyrrhenian Sea and formidable rivals to the Greeks and Phoenicians everywhere in The Mediterranean Sea, a true thalassocracy.

Etruscan advanced trade networks not only covered the Mediterranean but extended into northern and eastern Europe, and the Aegean. Etruscan artifacts have been found as far north as Sweden and as far east as South Russia. Exports included wine, olive oil, grain, pine nuts, wood, marble, copper, iron ingots, bronze ware, linen, pottery and fine jewelry. Imports included gold, ivory, ostrich eggs (which were decorated and exported), scarabs from Egypt, fine furniture, glass bottles, oil lamps, and pottery, especially fine Greek pottery from Attica, the southernmost peninsula of Greece that includes Athens and its countryside. This latter import was so popular that some were made especially to suit Etruscan taste. More Attic pottery has been unearthed in what was once Etruria than in all of Greece. The Etruscans made and exported their own unique earthenware pottery called bucchero. It was black and often highly polished (reminding me of the famous Maria Martinez pottery from San Ildefonso Pueblo just up the road from me). The styles and decoration of this and other red clay pottery evolved over time as the Etruscan and Greek ceramicists influenced each other.

Etruria was a collection of independent city states bound by a common religion, language and culture. They developed independently so that advances/changes in governance, manufacturing, art and architecture occurred at different times in different places, with the coastal cities evolving more rapidly owing to their greater contact with other cultures. Although a number of city states banded together into Etruscan Leagues these were not political or military alliances; they were more economic and religious confederations. Early monarchies gave way to oligarchies in most city states, with the chief magistrate – who was the civil, military and religious leader – elected for a proscribed period by the aristocrats and, later, a growing class of merchants and landowners who aspired to join the ruling oligarchy.

Numerous sources describe the Etruscan government as a theocracy and it does seem clear that their religion was a central force in daily life as well as a source of inter state cohesion. Like other ancient civilizations, the Etruscans were polytheists. Extensive iconography on tombs and vase paintings, statues, engravings on the backs of bronze mirrors, give scholars an idea of the Etruscan pantheon, a blend of elements of Greek and Italic mythology and beliefs. The fundamental belief was that the universe was ruled by the gods and the fate of humans was completely in their hands. All natural phenomena conveyed the intentions of the gods and required interpretation to comply with their wishes.

Roman historians considered Etruscans the most religious of peoples and called their system of beliefs and rituals Etrusca disciplina, where the Latin word disciplina means “a science.” It was a complex system of codified ritual that included special divination disciplines, as well as rules for interpreting signs and portents and the responses to them to avoid disaster and placate the gods. Latin writers frequently refer to three categories of sacred books none of which survived the burning of the books: the books of thunderbolts, the books of haruspicy (divination based on the examination of livers of sacrificed animals) and the books of rituals. The basis for the scared books were revelations given by the gods to humans through a divine child called Tages. Thus the Etruscan religion, like Judaism and Christianity, was a”revealed” religion, considered not the work of human beings.

Experts in the Etruscan national religious science, called, generically, haruspices, were from high ranking families and were recognizable by their distinctive dress. The sacred books were handled down from one generation to the next and special training institutes provided instruction not only in theology but in subjects ranging from astronomy to botany to hydraulics, more like a university than a seminary. Even after the Roman conquest of Etruria, the haruspices flourished as the Romans, impressed with the practical benefits of the Etruscan discipline, were quick to employ the skills of these specialists. Emperors and generals had haruspices in their retinue, to be consulted when some event requires ritual or divination. The Order of Sixty Haruspices, drawn from the nobles of various Etruscan cities was created by the Roman Senate and served as that body’s expert advisors.

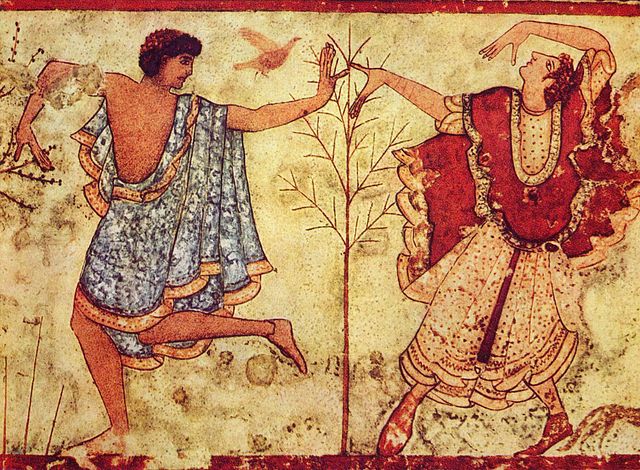

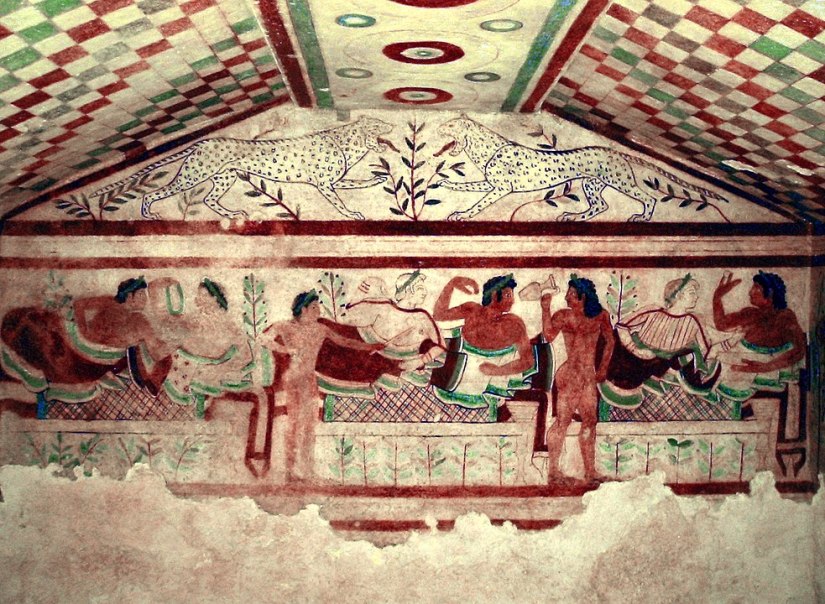

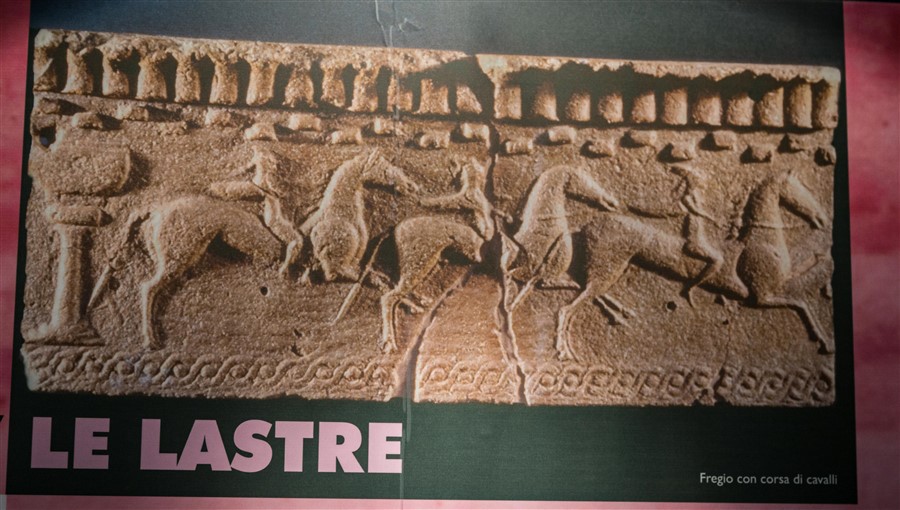

As mentioned above, the Etruscans were skilled potters, also goldsmiths, but for me the most compelling of their art was sculpture and painting. Unfortunately, what remains is mostly funerary sculptures and frescoes giving us a skewed view of Etruscan art since only the very wealthy could afford tomb wall paintings. Still, given the lack of written documents, we rely on these to gain insight into the Etruscan lifestyle, at least some parts of it.

Sculptures were of terracotta, bronze or alabaster, rarely stone. Many small terracotta figures have been pierced together from fragments and life size figures reclining on the tops of sarcophagi (also made of terracotta) have survived intact, although only traces of the polychrome painting are left.

Monumental terracotta statues of deities adorned the rooftops of temples, an Etruscan innovation.

Their contemporaries considered the Etruscans to be undisputed masters of bronze casting. Etruscan metal craft and bronze sculptures were prolific in Etruria and across the ancient world. Ancient historians report that 2000 bronze statues were taken in the looting of Volsinii by the Romans and then melted down to produce bronze coinage to finance their wars. Whether or not this is true it is testimony to the great wealth, luxury and art of that city. Many small bronzes and mirrors (which were cast as one piece, highly polished on one side and decorated on the back) have been recovered but almost nothing remains of the large statues. The stunning Chimera of Arrezo gives us a glimpse of what has been lost.

Much of what we know about Etruscan life derives from their many excavated tombs which, in the earliest times, were built with the assumption that the deceased would be active in the afterlife and thus have need for a dwelling complete with furniture, implements and decorations. Frescoes showed scenes from daily life, often banquets accompanied by dancing and music and games. Creatures and scenes from Etruscan and Greek mythology appear, and all of this in blazing technicolor.

From these depictions and other works, the Etruscans come across as a fun loving, artistic culture that held women in high esteem unlike their Greek and Roman counterparts. Etruscan women dined and drank and danced with their men, were free to go out in public, attend sporting events and public celebrations, ride horses astride, raise their own children. They were literate, had their own names and ranks and could inherit property; they were beautiful and flaunted their beauty in public, wearing fine clothing and fabulous gold jewelry. Etruscan priestesses and oracles, while not prominent in religious practice, were in the public eye, influencing politics by their prophesying or giving blessing to newly elected kings. It is this public face of Etruscan women that seems to have scandalized contemporary Greek and Roman writers who then proceeded to vilify them. Clearly, those intensely patriarchal cultures felt a threat to the status quo which they sought to neutralize by characterizing the Etruscans as uncivilized barbarians. Ironically, the Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized couple pairing and valued multi-generational family ties.

The seventh and final Etruscan king of Rome was overthrown in 509 BCE leading to the establishment of the independent Roman Republic which then attacked Etruria from the south. Maritime defeats and attacks on the port cities as well as invasion by Celtic tribes in the north continued the deterioration. By the mid 4th century BCE, the once dominant military and commercial power in the Western Mediterranean was reduced again to city states who failed to unite against a common enemy. Over a period of 234 years – years of wars, treaties, truces, alliances, sieges, counterattacks – they were picked off one by one by the more organized Romans. In the wake of those military defeats and the brutal colonization that followed much of Etruscan cultural heritage was lost.

Those following this site may have noticed the long period of time between the last several posts. Lay it all at the feet of those “mysterious” Etruscans! One of the sources I consulted warned that once introduced to this amazing civilization one may quickly become hooked on the subject. So it was with me. I found myself spending hours delving into one aspect or another, seeking multiple points of view and interpretation, drawing my own conclusions from the mix, then trying to succinctly describe what I had learned, a very slow process indeed. I ended up using more images from other sources (all credited properly) as this post became more about ancient history than travel. If I had done this research before going to Tuscany it might have been a very different trip.

In case you want to explore more here are some interesting web references.

Compared to other advanced ancient civilizations of the same era, such as Greek or Chinese, we know relatively little about the Etruscans who dominated central Italy for nearly half a millennium, from~800 to 300 BCE. Several factors contribute to this sorry state of affairs.

The Etruscan language is still a puzzle for modern linguists who can understand only a few hundred words. It has long been considered a language “isolate” and is not in the Indo-European family. Although early Roman authors refer to an extensive Etruscan literature, something that would help immensely in understanding the language, nothing readable remains. Various explanations have been advanced for this surprising absence: the intentional, systematic destruction of Etruscan literature by early Christians eager to stamp out “pagan superstition,” the fragility of the medium used to record writing, the natural extinction of a language not as widespread in the ancient world as, say, Greek. Probably all of these played a part.

The Etruscans left no imposing temples or amphitheaters, no substantial remains from which we might reconstruct towns or buildings. Domestic structures were built of wood and plaster, materials that do not survive over centuries. Many Etruscan towns lie beneath those built over them in medieval and later times making excavation for archeological purposes impractical.

Finally, it seems clear that the Etruscan civilization was completely overshadowed – some say obliterated – by the conquering Romans who, nevertheless, took many of their ideas on art, road building, city planning, water management, law, religion, architecture, even clothing. Indeed the toga, the familiar outer garment of Roman citizens, was appropriated from the Etruscans. Contemporary bloggers and Tuscan travel sites have taken up the cause of this amazing civilization, hoping to set the record straight.

Despite these obstacles, we know enough about the Etruscans to merit the admiring descriptors I have used above. How? Most of what we know comes from contemporary Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Middle Eastern sources.They are not without their prejudices but give us enough information to create a sense of Etruscan society, its history, structure, and functioning.

In addition, while the Etruscans left no temples, above ground tombs, usually small stone buildings but sometimes very large round structures, have been found. These may be furnished and decorated with magnificent, vividly colored wall paintings which give us a glimpse into their daily lives and social attitudes.

More about the Etruscans later.

Harvest festivals are common the world over and autumn in Tuscany sees many celebrations of Italy’s most popular foods: truffles, porcini mushrooms, chestnuts, pumpkins, olives and, of course, grapes. Some feste last for days and include vendors selling dishes that show off the newly harvested food. Others are evening affairs, often dinners where the food is cooked by locals and the proceeds support some local project or charity.

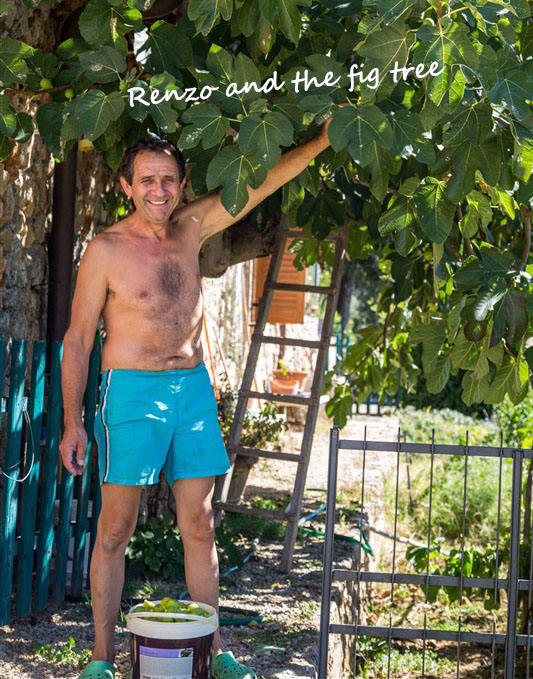

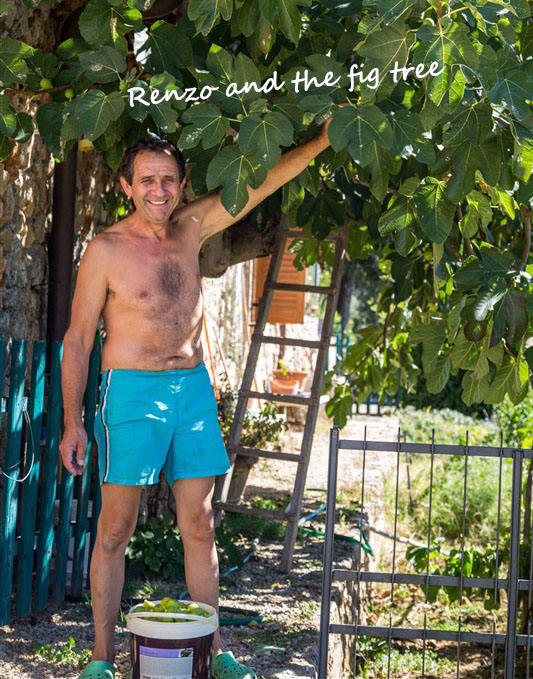

When we told Marzia and Renzo that we like going to food fairs and community celebrations they immediately swept us off to an evening harvest festival at the hamlet of Ponte a Tressa, about 30 minutes away. There, as we stood in line perusing the menu (which was in Italian, of course), a local was heard to say (also in Italian, of course), laughing, “Well, it’s looks like we’ve made it: the Americans are here!” This was reported by Allegra who with Renzo ordered for all of us, as the only thing we recognized on the menu was pizza. We sat at long tables and ate family style. The main ingredient was goose cooked several ways: goose stew, sliced goose, stuffed goose neck, With each dish came potatoes, also cooked in different ways. We had a variety of bruschetta as well as the ubiquitous pizza and, of course, vino. There was a live band and dancing, pens with farm animals, games of chance and a stand where Renzo treated us all to limoncello, an essential and delicious finishing touch to a meal.

The second festa, some weeks later, was different. For the Buonconvento event, we bought tickets to a sit down meal at a table the size of our party (4 in this case). There was a choice of two complete meals which were delivered to our table.The food was good but not unusual and I don’t remember what we ate. Live music and other activities happened around the historical center, including a well attended fashion show. Buonconvento is Marzia’s home town and her father, who was in his 80’s, joined us for dinner. Most memorable from this experience was our leave taking with Marzia’s father. Again I quote Joan’s journal: “When we parted for the night he held each of our hands and, as translated by Marzia, thanked us for coming and wished the best for us always. Even though I could not understand a word that he said to me, I could feel the warmth and sincerity of his words. Sometimes feelings transcend verbal communication.”

In any part of Italy one cannot help but observe the ubiquitous ecclesiastical structures: parish churches, monasteries, abbeys, hermitages, basilicas, many, perhaps most, still active after hundreds of years. In Tuscany even the smallest hamlet has a church and the region abounds with Romanesque, Medieval and Gothic religious buildings.

So what is an abbey? An abbey (abbazia in Italian) is essentially a monastery that is autonomous and governed by an abbot. It often includes a number of buildings – church, living quarters, refectory, cloister, library, agricultural structures – as well as landholdings. The abbot is likely to have more involvement in the surrounding community than, say, a parish priest or a prior. Abbeys were built across Europe in the Middle Ages according to a plan written by he founder of the Benedictine religious community. Tuscany, particularly Siena province, is rich in abbeys. Because they were often built in relatively secluded places and because they were meant to reflect the simplicity of monastic life, their architectural beauty set in a spectacular environment is immensely attractive, even if one is not religious.

We visited two of the most famous and beautiful active abbeys (Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore and Abbazia di Sant’Antimo), the breathtaking ruin of Abbazia di San Galgano and the remarkable cloister at Torri, now privately owned and open to the public only a few hours a week.

A bit of history and more images of these remarkable places are here.

Except for a day trip by bus from Siena to Florence, we drove our rented Fiat Panda from Pisa to Siena and all around the Tuscan countryside. I cannot describe the experience better than my spouse did in the journal she kept for the trip.

“We have a Fiat Panda, small but not tiny. It is a stick shift which neither of us have driven for years. Steph* did all of the driving the two weeks she was here and we either all went in their car or we followed in ours. No easy task as Steph is used to driving stick shift and could race for NASCAR. The roads are narrow, hilly and curvy. Actually, they are a series of S curves interrupted by a U curve on occasion. I have heard of the 7 hills of Rome but nobody told me about the 700 hills of Tuscany. I think we have been up and down all of them at least once.

Italians are very good drivers and you know one is behind you if you look up and see a car so close that you think you are towing it. Passing distances are short because of the curves and they get as close as possible before passing. Solid lines don’t matter. If they see a straight stretch of road they pass. There are also pedestrians walking on the road because there aren’t many sidewalks or they walk into a crosswalk even though you are coming at them at 30 mph. Then there are the cyclists riding on the narrow roadway.

But most distracting for me are the motor scooters. They drive right on the center line between cars and you don’t know where they in roundabouts since they move freely from right to left and visa versa.

We have had a few scares like when a truck is on our side of the road on a curve or someone is passing when they shouldn’t be. I have stalled out in the middle of an intersection and rolled backward when I wanted to be going forward. We both find ourselves in the wrong gear at times and I often forget to take the emergency break off, but all in all we are doing OK.”

*Our party consisted of my niece Allegra (who is fluent in Italian, often mistaken for a native) and her spouse Stephanie, my sister Lucretia, me and my spouse whose name is also Joan (aka JK). Marzia (who is fluent in five languages, including English) and Renzo are Allegra’s friends and our gracious landlords/hosts. Allegra, Steph and Lu stayed for the the first two weeks; we were on our own after that.

The hilltops around Siena are dotted with Medieval towns and hamlets, at least 200 of them having their ancient walls, fortresses and tower houses more or less intact. Cars are left in parking areas outside the walls and access to the center is on foot. Steep narrow lanes wind up and down the hilltops, the sturdy stone houses abutting them connected together, often fronted with flower boxes and plants.

Most towns have at least one Romanesque and/or Renaissance era church, often with stunning frescoes by master artists, and a main piazza with a town hall sporting a Gothic facade and a tall central torre. Inevitably – thankfully – restaurants and coffee bars ring the piazza.

Some towns can date their origins to Tuscany’s ancient (900-400 BC) people from whom their name derives, the Etruscans, and feature archeological ruins and artifacts in their Etruscan museums. Others have become famous for their wines and still others are, as Marzia called them, “unspoiled,” not frequented by tourists and so absent the crowds and the shops that cater to them.

We visited some of each. With Marzia’s help we identified Etruscan towns (which interested me), wine towns (which interested Joan), “unspoiled” towns, towns of particular beauty or historical importance, hot springs, ruins, active abbeys all the while enjoying iconic Tuscan scenery, from the Crete Senesi to the Maremma coast. Images from these excursions are here: Hilltop Towns, Hilltop Towns II, with more to come.

The Historic Center of Siena is a UNESCO World Heritage Site described as “the embodiment of a medieval city.” At its center is the public square, Piazza del Campo, widely regarded as one of the finest in Europe owing to its beauty and architectural integrity. It’s shaped like a scallop shell with the flat portion bordered with the Pallazo Pubblico, the historic seat of local government, and, rising from it, the magnificent Torre del Mangia,. The latter was built to match the height of the Duomo di Siena to signify that the church and the state were equal, having the same level of authority.

Siena was created when three communities that existed on three adjacent hills coalesced. At the intersection of the Y that delineated the roads to those communities and beyond, there was a valley that served as a convenient marketplace. This is the site of il Campo, as it is commonly called, meant to be a neutral territory for activities, games and political and civic holiday celebrations. Its present form was created in the mid-14th century with deliberate intention to establish harmony between the buildings and the square. The palatial homes of Siena’s ruling elite lining the square were required to have uniform roof lines in contrast to the earlier tower houses, symbols of community strife.

The Piazza was intended as an area where the entire population of the city could attend activities. The population of Siena in its golden era has been reported as between 50,000 and 80,000. Today, for the Palio, 28,000 people cram into the center and another 33,000 line the perimeter.

The red brick herringbone paving of the Piazza slopes slightly downward, inviting one to simply sit down as if at a beach or amphitheater, and that is exactly what people do. It is possible to climb the 400 steps up the Torre del Mangia but I did not attempt that even knowing spectacular views of the city and the countryside were in the offing. Below is an image, not mine, taken from the top of the tower, to give you a feel for the magnitude of this splendid town center.

If you have been to Florence you will have been impressed by the immense cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore, with its polychrome marble exterior and extraordinary dome. Siena’s cathedral, dedicated to Santa Maria Assunta, is not as large but boasts a most fascinating facade and an eye popping interior.

Compare the interiors of the two cathedrals, Siena’s on the left, Florence’s on the right.

The magnificent Duomo di Siena rises from a piazza atop one of the three hills above il Campo. Legend has it that it was built on the site of a 9th century Christian church which in turn had been built over a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva. Construction started in 1200; records show masses being held as early as 1215 and the main sections completed by 1264. Much of the exterior and the entire interior are sheathed with alternating layers of white and greenish-black marble. Black and white are the colors of the Siena coat of arms, arising from a foundation story that links the city to a noble and ancient ancestry.

Built in two stages, the lavish facade is a combination of French Gothic, Tuscan Romanesque and Classical architecture. The lower facade, (1284-1296) with its three portals is covered with sculptures of prophets, sibyls, mythical animals and gargoyles, the work of Giovanni Pisano. The upper facade, which was finally completed some 60 years after Pisano left Siena for Pisa, features heavy Gothic decoration.

The interior is a dazzling collection of sculpture, painting, stained glass, inlaid wood and mosaics. One hardly knows where to look first. I visited the Duomo on two occasions but could have spent the entire month exploring its treasures. For me the most impressive and beautiful of these treasures are the mosaics that completely cover the floor, 56 interlocking slabs covering 14,000 square feet, depicting scenes from Classical antiquity, the Old Testament, allegories, all of which meant to send a message of salvation and wisdom to the viewer. It is now possible to climb above the vaults for extraordinary views of the interior and exterior. Once again I rely on an other’s stamina to provide you with a glimpse of the extent of the unique marble mosaic floor.

Find more images of Siena and it storied art and architecture by looking here.