Getting Around to

Feste

Harvest festivals are common the world over and autumn in Tuscany sees many celebrations of Italy’s most popular foods: truffles, porcini mushrooms, chestnuts, pumpkins, olives and, of course, grapes. Some feste last for days and include vendors selling dishes that show off the newly harvested food. Others are evening affairs, often dinners where the food is cooked by locals and the proceeds support some local project or charity.

When we told Marzia and Renzo that we like going to food fairs and community celebrations they immediately swept us off to an evening harvest festival at the hamlet of Ponte a Tressa, about 30 minutes away. There, as we stood in line perusing the menu (which was in Italian, of course), a local was heard to say (also in Italian, of course), laughing, “Well, it’s looks like we’ve made it: the Americans are here!” This was reported by Allegra who with Renzo ordered for all of us, as the only thing we recognized on the menu was pizza. We sat at long tables and ate family style. The main ingredient was goose cooked several ways: goose stew, sliced goose, stuffed goose neck, With each dish came potatoes, also cooked in different ways. We had a variety of bruschetta as well as the ubiquitous pizza and, of course, vino. There was a live band and dancing, pens with farm animals, games of chance and a stand where Renzo treated us all to limoncello, an essential and delicious finishing touch to a meal.

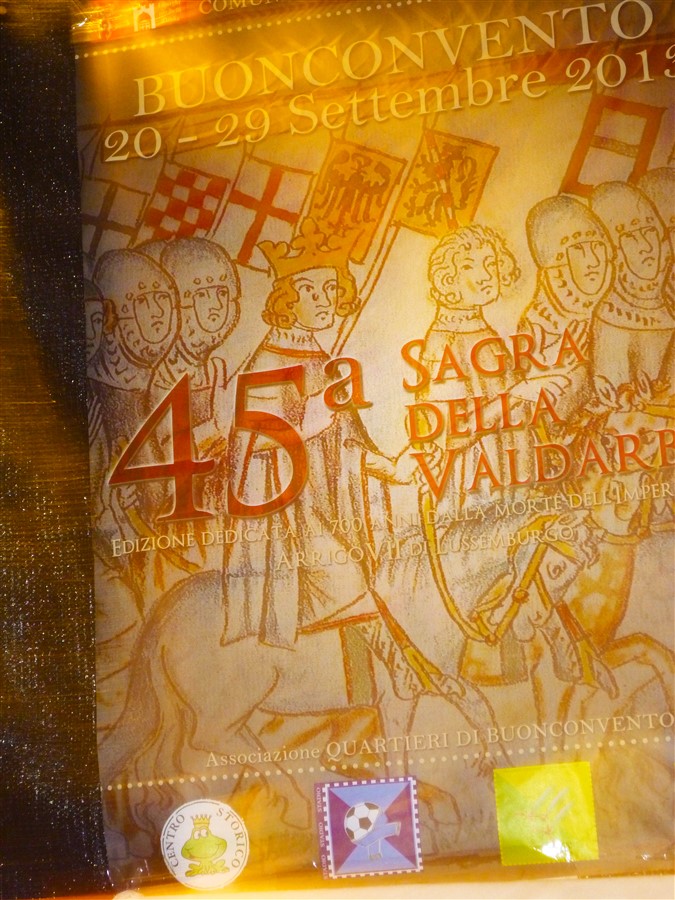

The second festa, some weeks later, was different. For the Buonconvento event, we bought tickets to a sit down meal at a table the size of our party (4 in this case). There was a choice of two complete meals which were delivered to our table.The food was good but not unusual and I don’t remember what we ate. Live music and other activities happened around the historical center, including a well attended fashion show. Buonconvento is Marzia’s home town and her father, who was in his 80’s, joined us for dinner. Most memorable from this experience was our leave taking with Marzia’s father. Again I quote Joan’s journal: “When we parted for the night he held each of our hands and, as translated by Marzia, thanked us for coming and wished the best for us always. Even though I could not understand a word that he said to me, I could feel the warmth and sincerity of his words. Sometimes feelings transcend verbal communication.”

Abbeys: Active, Inactive and Ruined

In any part of Italy one cannot help but observe the ubiquitous ecclesiastical structures: parish churches, monasteries, abbeys, hermitages, basilicas, many, perhaps most, still active after hundreds of years. In Tuscany even the smallest hamlet has a church and the region abounds with Romanesque, Medieval and Gothic religious buildings.

So what is an abbey? An abbey (abbazia in Italian) is essentially a monastery that is autonomous and governed by an abbot. It often includes a number of buildings – church, living quarters, refectory, cloister, library, agricultural structures – as well as landholdings. The abbot is likely to have more involvement in the surrounding community than, say, a parish priest or a prior. Abbeys were built across Europe in the Middle Ages according to a plan written by he founder of the Benedictine religious community. Tuscany, particularly Siena province, is rich in abbeys. Because they were often built in relatively secluded places and because they were meant to reflect the simplicity of monastic life, their architectural beauty set in a spectacular environment is immensely attractive, even if one is not religious.

We visited two of the most famous and beautiful active abbeys (Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore and Abbazia di Sant’Antimo), the breathtaking ruin of Abbazia di San Galgano and the remarkable cloister at Torri, now privately owned and open to the public only a few hours a week.

A bit of history and more images of these remarkable places are here.